Beyond the Classroom: Texas City High’s Empowering Experience at Student Legislative Seminar

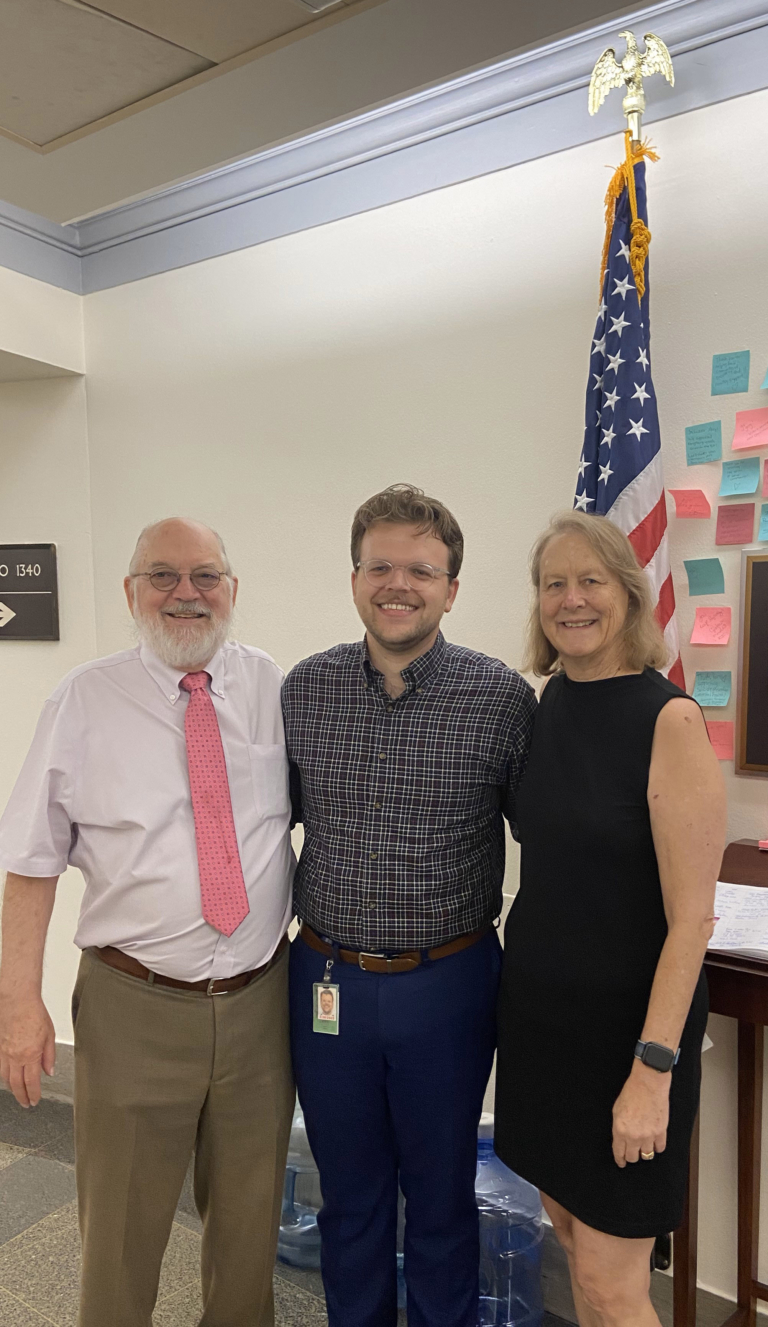

March 2-7 saw twelve students and three teacher chaperones from Texas City High School in Washington, DC for one of the Institute’s Student Legislative Seminars. This is the 13th time Texas City has participated in this program, and with chaperones who have experienced the trip before on hand with us again, the trip just keeps…