Marriage Equality, Suspicion, and Insular Thinking

A fair amount of uncivil discourse has passed through the American public sphere since the end of June when, in their decision on Obergefell vs Hodges, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment requires a State to license a marriage between two people of the same sex.

Ken Paxton, Attorney General of Texas, almost immediately released a non-binding legal opinion which, according to Robert Garrett of The Dallas Morning News, stated that clerks could refuse on First Amendment grounds to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples because, as he says, of their religious objections. Paxton added in a press release that there are numerous lawyers who stand ready to assist clerks defending their religious beliefs, in many cases on a pro-bono basis, and that his office, too, stands in defense of their rights.

And Ken Paxton is not alone. In Tennessee, the beginning of July saw the entire staff of the county clerk’s office of Decatur County resign on religious grounds. In Nebraska, Sioux County clerk Michelle Zimmerman said that she will deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples because her religious beliefs prevent her from complying with the law. And in Kentucky, county clerk Casey Davis has called on the state legislature to pass a new law allowing couples to purchase marriage licenses online, so as not to have to violate his religious beliefs by issuing the licenses himself.

These cases in themselves are not inherently uncivil. Freedom of religion is a fundamental right in the United States, and it certainly seems worth having a frank conversation about how to implement this change in the interpretation of the law while respecting, to the greatest degree possible, everybody’s interests.

But in practice, these cases and the discourse that surrounds them are a perfect example of the kind of incivility that is born of a breakdown of communication. All parties are so busy talking to their ideological in-group, and so busy indulging their ideological in-group’s preconceived notions, that nobody can hear the other side speak.

And so when social conservatives over the past several weeks have stood up for religious freedom, too often pro-gay marriage factions have jumped to the least generous possible conclusions. And conservatives have jumped to that same ungenerous place when progressives have celebrated what seems very much like an affirmation of their identity, needs and beliefs.

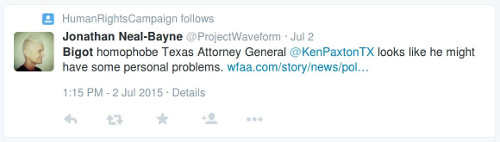

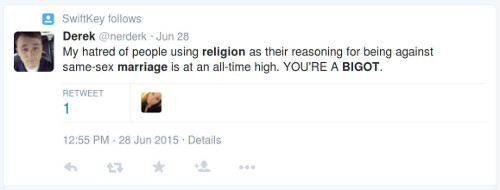

To see the kind of vitriol this produces, one needs only look at the blanket accusations of bigotry bandied about on Twitter by folks who support the Obergefell ruling.

And one needs only look at the kinds of suspicious discourses bandied about by Obergefell opponents. According to The Daily Caller, Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal called the Supreme Court completely out of control, and said that the Obergefell decision amounted to an affront to God, country, and political affiliation. Hillary Clinton and The Left will now mount an all-out assault on Religious Freedom guaranteed in the First Amendment, Jindal opined.

While in his dissent on the case, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito falls into the slippery slope fallacy, writing that the ruling will be used to vilify Americans who are unwilling to assent to the new orthodoxy, and that those who cling to old beliefs will be relegated to whispering their thoughts in the recesses of their own homes for fear of public persecution.

The sad part about it is that each side seems to be proving the other right. Alito worries that opponents of gay marriage risk being labeled as bigots for their views, and that’s exactly what we’ve seen on Twitter. While progressives fear that resistance to the Supreme Court’s ruling is born of narrow-mindedness, and we’ve seen plenty of that, too. When former Arkansas governor and current presidential candidate Mike Huckabee says that legalization of same-sex marriage would lead to the “criminalization of Christianity,” and that the country “must resist and reject judicial tyranny,” what else should supporters of marriage equality think?

A solution to this – if in fact we collectively want one – exists in reconsidering the purpose of speech. Is the goal of public discourse merely political in the lowest sense of the word? Is it meant to score points, secure donors, and collect votes with the hope of getting elected the next time around? If so – if we want only to talk to the people who already agree with us – then the status quo works fine.

But if Ken Paxton and county clerks around the country are sincere in their concerns, and if a significant portion of the citizenry of the United States feels that their religious freedom is being trampled on by the Obergefell ruling, then speech might have to mean something broader: it might have to mean being quiet and listening, too.

For those of us who work on civility, the Institute’s definition of the term – that is, claiming and caring for one’s identity, needs and beliefs without degrading someone else’s in the process – is almost a mantra: words repeated by rote, filled as much with ritual meaning as with relevant content.

But the Institute’s definition is certainly relevant here.

It’s time for uncivil progressives to take a break from sneering at social conservatives who look at the Bible, or the weight of history, and decide that same sex marriage really has no precedent. And it’s time for uncivil social conservatives to stop dismissing claims from same sex couples that what they want is only what everybody else already has. If we read beyond the insularity and fear, what both sides are expressing is that they want to have their identity, needs, and beliefs respected and protected by law. And through civil discussion – the sort of discussion where every party comes to the table honest about its desires and motivations – a solution where all sides can get what they want is far from beyond the realm of what’s possible.

This is a good, thought-provoking article for help in understanding and processing all we hear and read.

Kathleen Riley Goeppinger liked this on Facebook.